Welcome to Moda!

Day of the Girl: Meet Harriet!

Day of the Girl: Meet Harriet!

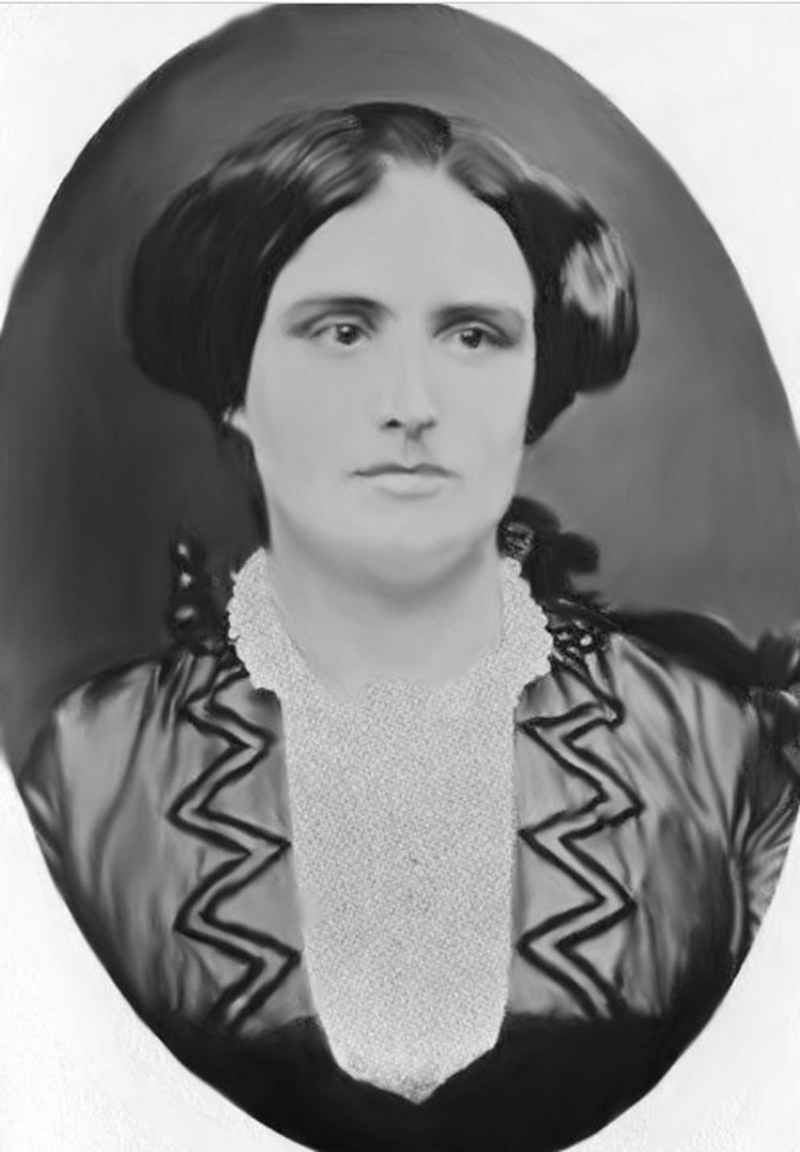

There’s no better day than today—the International Day of the Girl—to “meet” Harriet Hanson Robinson, the mill worker, suffragette, poet, and advocate for worker’s rights, who inspired Betsy’s Chutchian’s newest fabric line.

A lifelong love of history spurs Betsy to base her fabric lines on the stories of woman who lived during the same era that the fabric designs were originally produced. For Harriet’s Handwork, drawn from the fabrics in a simple nine-patch quilt from the 1820s-1840s, Betsy remembered the mill workers of Lowell, Massachusetts and was intrigued to learn about Harriet, who was born in 1825.

As one of four children, Harriet Hanson had a challenging childhood. Her father died when she was just six and her widowed mother supported the family by operating a small store. All five family members slept at the back of the shop in the same bed “two at the foot and three at the head” as Harriet later wrote. When the venture failed, the family moved to Lowell, Massachusetts, a factory town at the convergence of two rivers.

To satisfy workforce needs, the Lowell mills brought in girls from the surrounding countryside, built dormitories to house many of them, and created religious, cultural, and educational activities to fill their evening hours. Harriet’s mother took a job managing a boarding house and at age ten Harriet went to work in a mill as a doffer, replacing the bobbins filled with newly spun wool with empty ones. She earned $2 a week and because the job required just 15 minutes of her attention every hour, she was left with time to read. (Many of the “Lowell girls” had an interest in education and appreciated the access to books and evening lectures the mills provided.)

At the age of 11, Harriet was one of the first to strike (or “turn out” as it was then called) when the wages of mill workers were reduced. It was 1836 and though she admitted later to some “childish bravado,” it was an action of which she was proud. It was also the beginning of a lifelong activism related to the lives of workers and particularly of women workers. Harriet admired their work ethic and the empowerment that earning money gave them, and felt that the poor could be just as hardworking and worthy as the wealthy.

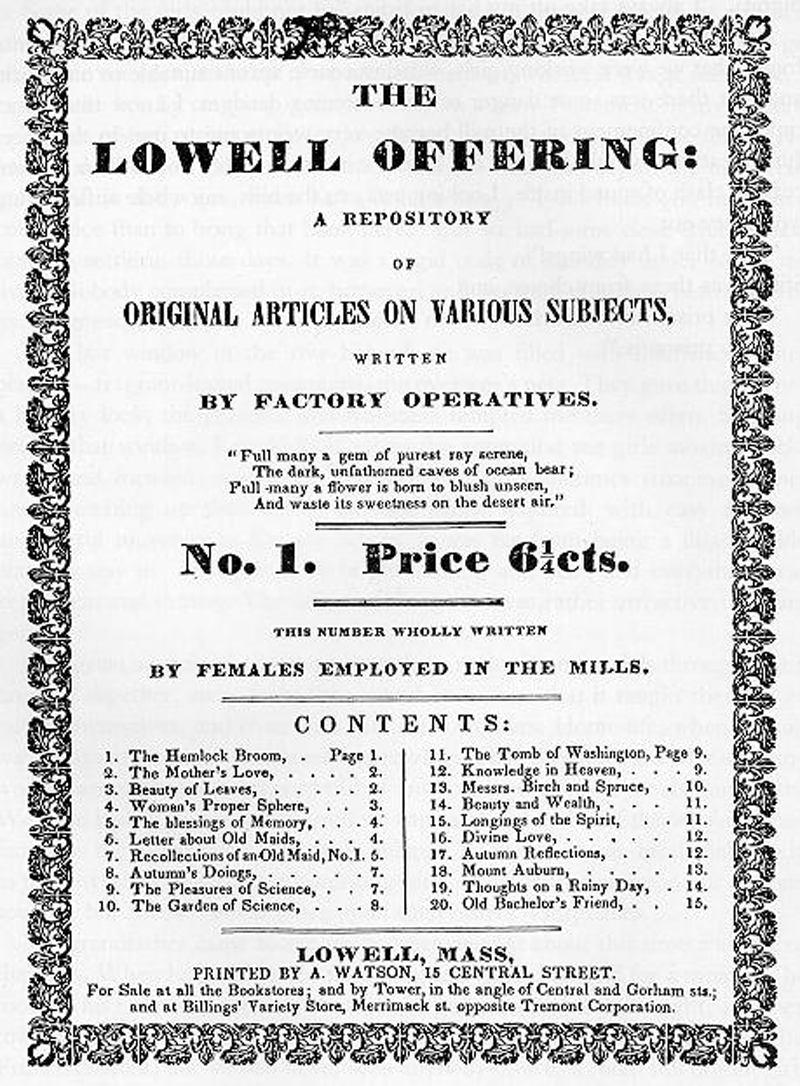

When she was 15 she left the mills for two years to enroll in high school, where she wrote an essay called “Poverty Not Disgraceful.” She returned to the mills but also wrote poetry, some of which was published in the Lowell Offering, a magazine that published writing by the Lowell girls, and the Lowell Journal. It was there that she met her husband, editor William Robinson.

They were married in 1848, when Harriet was 23. Marriage meant the end of her mill days, though her awareness of the mills' worsening conditions, including long hours and unsafe surroundings, continued.

Harriet and William cared for their four children (one died in infancy) and for Harriet's mother. They struggled to make ends meet and when William died in 1876 Harriet rented out rooms to boarders. She also continued to write and her book Loom and Spindle, which details the positive conditions created for the early mill girls, is still read today. Harriet and one of her daughters also became involved in the suffrage movement, organizing the National Woman’s Suffrage Association of Massachusetts, and she even testified before Congress on the subject of suffrage. Sadly, she didn’t live to see women get the vote in 1920—Harriet Hanson Robinson passed away in 1911.

When asked about the appeal of Harriet’s story, Betsy’s response comes after a thoughtful pause. “She did not give up,” says Betsy. “She wrote articles throughout her lifetime about honest, hard labor being good for women, good for everyone. Harriet was not a quitter and she showed a lot of strength. There is so much we can learn from the lives of women.”

Now that you know about Harriet, stay tuned—next week we'll share more about Harriet's Handwork!

Comments